Review #3: Being Borrowed, or a Chance to Extend Ropes

Nadia Mounier

“Being Borrowed; On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf” is a group exhibition with works by Nourhan Abd El-Salam, Aya Bendary, Omar Mansour, Farida Rady, Tasneem Gad, Doha Aboelezz, Farida Serageldin, Khaled El Demerdash, Hossam Gad, Eman Magdy, Lina El Shamy, Sally Abo Basha, Mariam Diefallah, Carlos Estrada-Ruiz, Nahed Nasr, Azza Solaiman, Zeina Belasy, Khaled Othman, Mohey Eldin Yehia, Ali Zaraay, Ibrahim Mohamed, Yasmina El Kamaly, Nadine El Banhawy, Tariq Abdalla. The project is a result of months-long workshop by Farah Hallaba (Anthropology Bel3araby), and the exhibition is curated by Farida Youssef, runs at Contemporary Image Collective (CIC) in Downtown Cairo from 2 - 31 October, 2022.

At first, I was unsure if I would be able to write about the exhibition due to the specificity of the topic and whether I would be able to engage with it effortlessly. To my surprise, as soon as I visited Contemporary Image Collective, where the exhibition was held, I was immediately engrossed by the exhibition and the projects presented in an instantaneous manner.

It was evident throughout the works on display and the texts accompanying the exhibition that in every Egyptian you can find at least one member who travelled to work in the Gulf or temporarily migrated there. I witnessed this when I was young with my uncles, and I remember constantly asking about their return to visit. I couldn't grasp the possibility for them to move back to Egypt permanently. Their absence was a constant and the only hope for their return was during vacations—for short intense visits. Family gatherings were centered around their presence and would stop only when they leave. The title of the exhibition “Being Borrowed; On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf” brought back hazy memories of conversations revolving around intentions of going back home—“We’ll be returning right after the children grow up a little”.

The title is humorously borrowed from the well-known film “Kharaga wa lam ya'ud (Gone and Never Came Back)” by Mohamed Khan, starring Yehia El-Fakharany, Laila Elwi and Farid Shawqi. Despite the difference in the character played by El-Fakharany about the structure of Egyptian families who migrated to work in the Gulf region, the film’s name has resonance in popular culture that allows for an easy understanding of the implied meaning.

The title is humorously borrowed from the well-known film “Kharaga wa lam ya'ud (Gone and Never Came Back)” by Mohamed Khan, starring Yehia El-Fakharany, Laila Elwi and Farid Shawqi. Despite the difference in the character played by El-Fakharany about the structure of Egyptian families who migrated to work in the Gulf region, the film’s name has resonance in popular culture that allows for an easy understanding of the implied meaning.

“Being Borrowed; On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf” is a smart title for the exhibition as it engages the viewer almost right away, like a commercial product that aims to attract its consumers in line with their popular culture references. In a similar manner, the curation of the exhibition by the organisers succeeded in communicating with the audience in a hospitable way, confirming that “the house is always open for loved ones”. Besides the guest book presented by the entrance, an old walkman was put up for use by visitors, inviting them to leave a sound recording if they wish instead of writing. Despite the simplicity of this detail and its connection with voice notes of the current times, it also engages the visitor directly with its symbolism of expatriates' habits back then.

The exhibition had a great turnout, not only for its relatability with many Egyptian families, but because of the careful interactive and immersive details and pieces presented. The curator’s decisions, Farida Youssef, helped mediate smoothly between the exhibited works and the public. Farah Hallaba, the founder of the Anthropology Bel3araby and facilitator of the workshop—that culminated with the exhibition—worked alongside Youssef on being present almost daily at the CIC during the entire duration of the exhibition, which lasted a month. Their presence provided an indispensable opportunity to engage with the public, share stories and experiences, and allow space for the exchange of knowledge on the temporary migration experience.

Installation view, photo by Ali Zaraay, “Being Borrowed”, 2022

Installation view, photo by Ali Zaraay, “Being Borrowed”, 202221 works were presented, ranging between video works, installations, many photographic archives as well as installations of readymades. Most video works were shown sequentially on loop on a large and relatively old television. 7 videos were shown that dealt with ideas of immigration to the gulf, complexities of distancing from family, the role of the father as the family’s anchor, and long-distance arranged marriages. This group of artworks relied on family relationships; what is the fine line between enforcing the artists families personal lives in the work and them being part of the intervention? How can we reflect on and understand the relationship with parents with ease? And how can they understand the use of art as a tool to express that intimate relationship?

Most videos were short, using a variety of simple montage methods, mainly based on the use of family photographic archives in their various forms. They open up a way of thinking about the importance of private archives as a source for interpretation of collective memory, and of the mobile phone as a source of a living archive. The sequence of one video after the other felt like viewing reels on any social media applications nowadays, such as those used in TikTok. There is a new language in our understanding of the moving image, that is greatly influenced by the daily productions of memes and posters taken from Egyptian film scenes, especially those in the period from the eighties until present time. This merge between documented scenarios and the style of handling, added an element of freshness and originality to the work. It expresses the struggles of this generation, and their attempts in understanding the challenges they went through with their families, perhaps without a full awareness.

Aya Bendary - The Carrier, photo by Ali Zaraay, “Being Borrowed”, 2022

Aya Bendary - The Carrier, photo by Ali Zaraay, “Being Borrowed”, 2022This was addressed in Aya Bendary’s “The Carrier” in the next room, where it appeared as if an explosion of ideas scattered out of a suitcase. In spite of its simplicity in artistic expression, the work was able to express her attempt to extrude and assimilate her memory and experiences with diaspora. There is a personal presence in most of the artworks by their respective artists, as if they are all portraits of them, which again helped relate the exhibition with the project. “Unspecified” by Omar Mansour, is the artist’s desk as a psychiatry student presented in the exhibition space, aiming to show his lengthy research on the mental health of adolescents upon their return to Egypt after a long absence. The viewers are invited to sit and interact with the papers and notes presented, even add to them if they may. The desk appears to be in a chaotic state, as if he is searching for something that is missing; here the work of art appeared not in what was on the desk, but in his search for something he did not yet know.

The presentation of archives moved from one mode to another with each room of the exhibition. If the video works appeared to be light and humorous in nature, the subsequent works spoke in a heavier manner, where I faced confusion and difficulty in digesting the experience. In "Place of Birth: The Sultanate of Oman" by Nourhan Abd El-Salam, the artist spoke about her separation from her childhood friend and the difficulty of travel procedures in a multidisciplinary approach. The work appeared to be told from a child’s perspective, where events are intertwined and erased as if it were a dream.

Themes of summoning memory and saving it from oblivion continues in the work of Farida Rady, Doha Aboelezz and Eman Magdy, as their artworks seem to be a form of participatory game, through which they evokes your memory of places, language, childhood and identity. Whereas the project, “That Memory Doesn’t Exist” by Tasneem Gad, created a context that could be real or imagined by recounting photos taken by her father during his employment in the Gulf. Gad invites visitors to share their memories with her, even those memories that haven't yet happened but that they hope they do so one day.

These projects feed into recent trends in the production of participatory work with the public, particularly in private art spaces, which however isn't a new phenomenon for local exhibitions such as the Youth Salon and the Cairo Biennale. It is not unusual for the nature of these exhibitions, which are always characterised by the oddness of the size of artworks and their concepts, as well as their production scale or display in the exhibition space. Their presence, however, in what we call independent contemporary art spaces, was not as widespread during the previous years as it is now. This type of work almost removes some burden from their artists, it is as if it destroys the concept of the sole artist, and invites the audience to complete the work and be part of it, so that everyone has a share in the narrative. This group though revealed another dimension to me that might explain this trend, which is the strong absence of public spaces where we meet and share our ideas together. Upon browsing the messages left by Gad or reading the instructions for the game "Same Same Ya Sadij" by Doha Aboelezz, one sees an attempt to weave a social fabric that expresses the inevitability of meeting and communicating with each other for a more accurate narration of our experience. We have a lot to talk about, to unpack and re-understand its context, but that does not happen due to the restricted public sphere. The artworks did not stop me artistically, but due to the importance of the medium as a creative decision, that stirs necessary discussions among all practitioners in the artistic field about the needs of this generation and trying to find a link with previous ones.

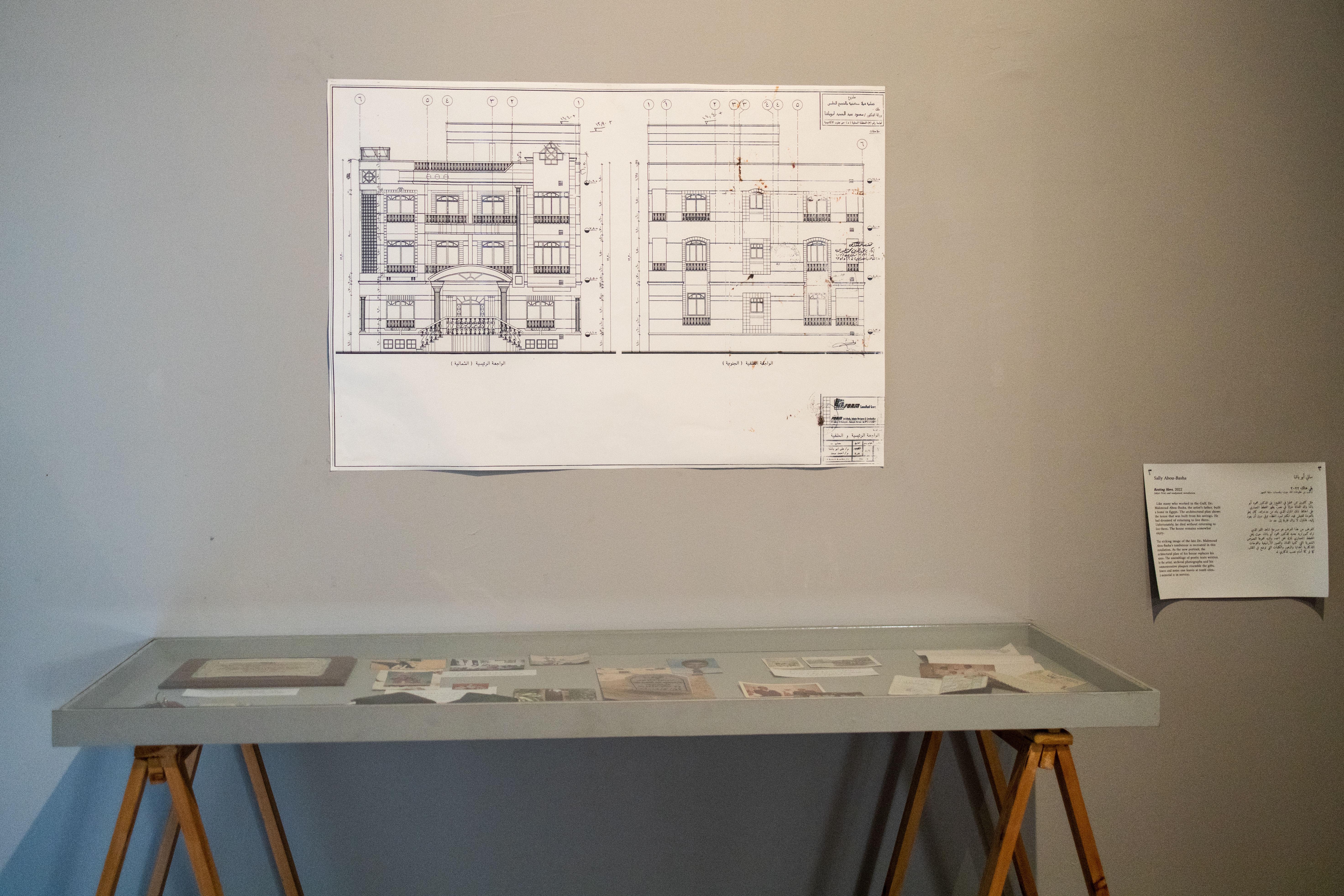

As the works in each room carry a specific idea of understanding the experience of migration, even if temporary, each room passes on a symbol that cannot be ignored to the other. In the fourth room, there is a strong presence of the image of the father and his symbolism at the top of the family hierarchical pyramid. In Hossam Gad's project "Ordinary Worker", he shows three relatively large photos of his father, cut from his passports over the past years. The official passport photo and the father's fixed gaze made the confrontation with him direct and intense. His seriousness in the pictures confused me, it made me feel the weight of the experience, and the deeds piled up in my mind. I recalled the father's voice in the video "Hear me, Aya?" which was said to Zeina Belasy at the beginning of the exhibition, where he advises her in his firm voice to listen and obey her mum’s words. Another example was the voice of Nahed Nasr imitating her father in her movie “Al-Qafdafi’s Birthday Cake.” The father’s symbolism reached its climax in Sally Abo Basha’s work “He Stayed There,” where she represented the loss of her father in the form of an architectural plan of the house he built in Egypt for their return, but never had the chance to go back and complete it himself. The project appeared as a memorial, not to the lost father, but to the journey and its lost heroes.

Sally Abo Basha - He Stayed There, photo by Nadia Mounier, “Being Borrowed”, 2022

Sally Abo Basha - He Stayed There, photo by Nadia Mounier, “Being Borrowed”, 2022Impressive is the ability of photography to fix or recall memory in a sudden manner that carries with it the accumulations of time. Despite the privacy of the projects and their association with their producers, they were able to cross the dividing line of privacy to intertwine and intersect with many other experiences that had something to say, but were not fortunate enough to have the space to express it.

The migration project to the Gulf started with a workshop that lasted for three months, in addition to the exhibition “Being Borrowed; On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf”. There is also a publication and a programme of events that showcase the experience of migration to the Gulf from different perspectives. It is as if the narration provided an opportunity to reimagine the interpretations of memory and collective history, to emphasise the project’s participation and everyone’s contribution to its artistic and cognitive production.

Nadia Mounier (b.1988, Cairo) is a visual artist working with photography and video. Her work is interested in representations of the self by exploring aspects of privacy, censorship, digital stagings, and body performance within the public and private spheres. As a cultural practitioner for the last 10 years, she is passionate about modes of collaboration, collective work, and alternative art programs. She is part of various art collectives that are interested in the city, image production, motherhood, and politics of representation. She was granted the Goethe Institute fellowship at Akademie Schloss Solitude in 2018 (DE) and Braunschweig Projects at HBK Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig in 2019 (DE). Her work was shown at Museum Rietberg, Zurich (2019), and the Museum of Photography, Braunschweig (2012). She also participated in a number of local and international exhibitions and festivals, e.g. PhotoCairo 6th edition (2017) Cairo, The Marrakech Biennale 6th (2016) and “Autonomy of Self” (2015), London.