Review #2: Pièces Détachèes

A. George Bajalia

“Pièces Détachèes” is a solo show featuring the work of Nassim Riad Azarzar, drawing from his ongoing research and practice as well as the results of his residency at L’Appartment 22 in Rabat, Morocco. It runs from August 26 to September 22, 2022.

“Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me, as is ever so on the road.”

Jack Kerouac, On the Road, 1957.

This exhibition emerges from Nassim Riad Azarzar’s years-long inquiry into the codes, signs, and symbols of Moroccan commercial transport trucks. “Bonne Route,” as the broader project is called, emerged out of the artist’s initial inquiries into the vernaculars of informal design and aesthetics, their formalization, and their circulation in 2018. Throughout residencies, exhibitions, and research periods, Azarzar’s work on the subject has taken forms such as digital projections, paintings, and these intimate drawings. I say intimate because, having seen a number of these iterations, I am struck by the intimacy of this exhibition. It is as if the visitor is invited into Azarzar’s studio to see the ongoing fruits of his labor over the past four years. Indeed, the drawings and sketchbook displayed alongside them appear to me to be an invitation into the artist’s ongoing research process and practice.

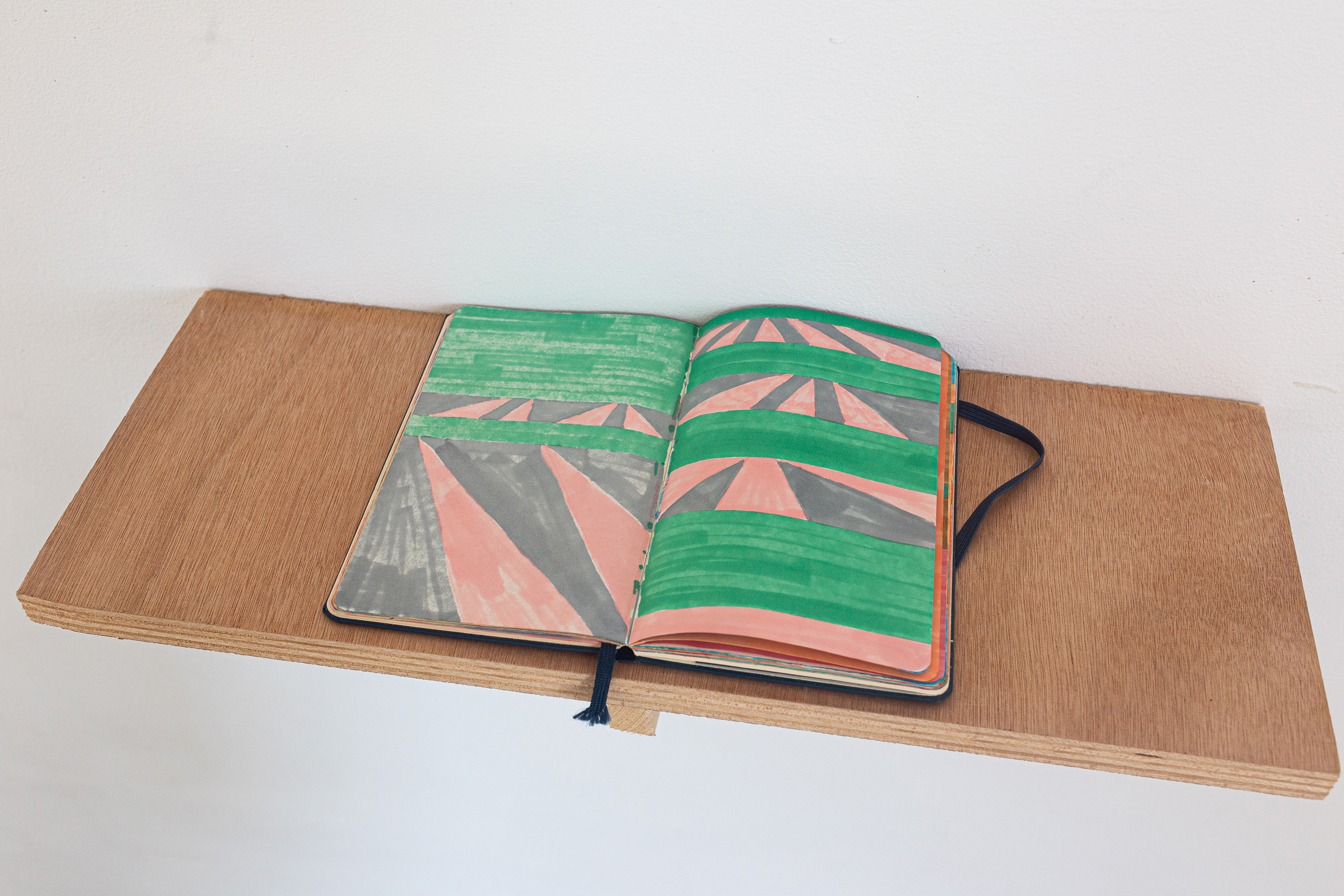

The show consists of 40 colored-pencil drawings that depict and depart from the signs and symbols Azarzar has collected over the years of his research into the aesthetics of Moroccan trucks and the visual vernaculars of their drivers and designers. Alongside these, the artist’s sketchbook shows his daily meditations on the theme with quick drawings done to put to paper visual representation of semiotic ruminations. The drawings range from direct repetitions of the shapes that decorate these trucks to deep purple, orange, green, and pink reflections of the horizons onto which such drivers gaze for hours on end, and which at times also adorn the trucks’ rear bumpers. The shapes and symbols repeat across drawings and across the four years in which Azarzar produced them. To search for a logic of the image is to search erroneously across the comic book style frames. Instead, the viewer might consider letting their gaze wander from symbol to symbol and letting the movement from point to line to perspective draw their imagination to the horizons just out of reach of the frames. While the installation of the pieces on the walls may invite some desire to find some order or logic to the repetition of symbols, this, to put it bluntly, misses the point. The repetition is the logic. The order of being of these symbols is their modes of circulation, and not a narrative structure.

Installation view, coloured-pencil drawings. (Photo Credits: Nassim Azarzar)

Installation view, the notebook of the artist. (Photo Credits: Nassim Azarzar)

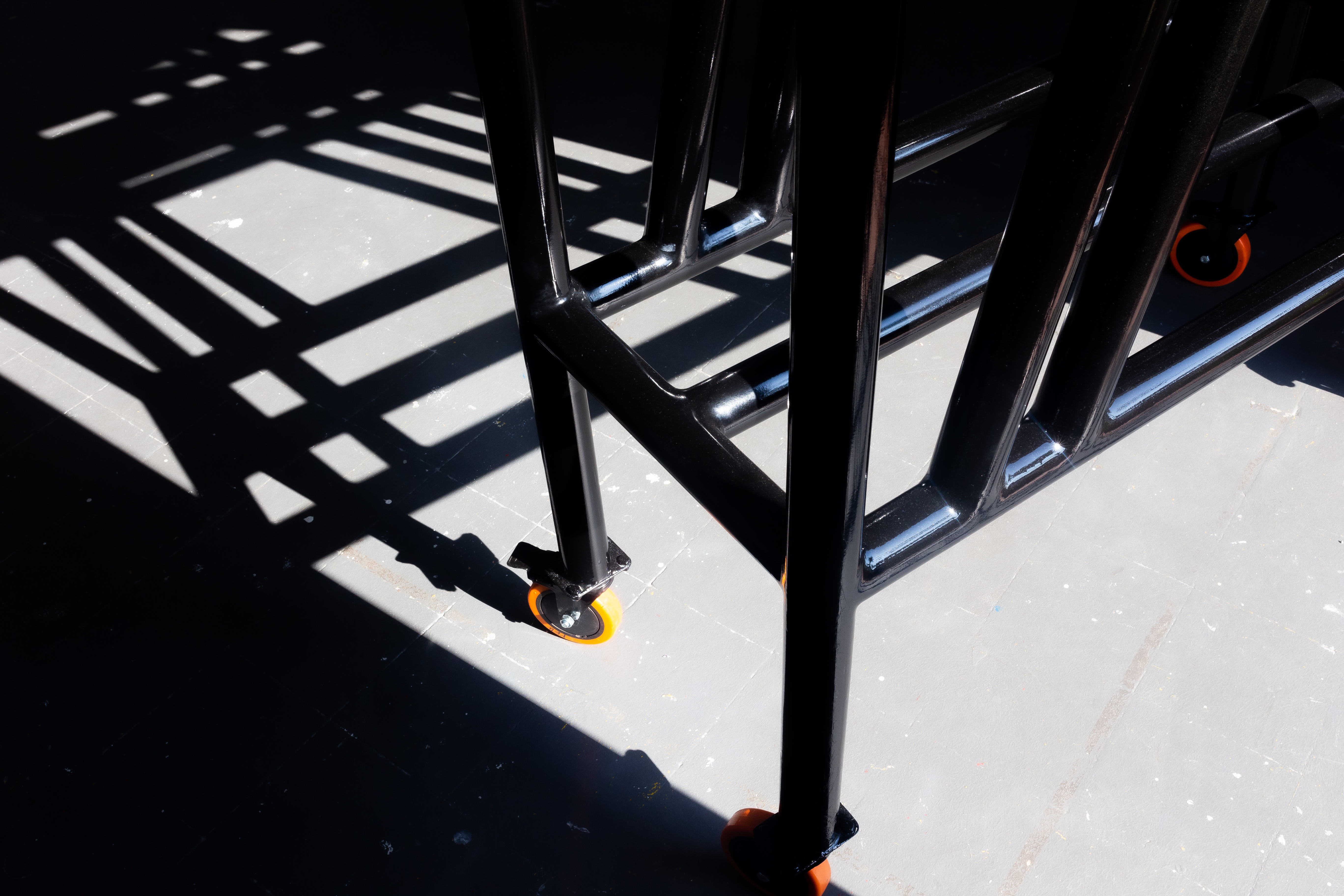

In the center of the gallery, a large black scaffolding—130 cm x 120 cm x 50 cm—sits imposingly on wheels. The scaffolding evokes the ubiquitous sites of buildings in progress across the country, and comes from the collaboration of Azarzar with master ironworker Abderrahim at L’Appartment 22’s production hangar in Fez. Finished in deep black paint, the lines of the scaffolding draw the eye to the perspectival angles that appear in so many of the drawings. Echoing one to another—the reflection of the drawings in the black, the shadow of the black lines spilling onto and across the walls of drawings, and the viewer’s eye peering through the lines of the scaffolding like a telescopic lens toward the drawings—the pieces sit in an uneasy tension. One might be tempted to wonder, just how do these parts fit together?

The name of the exhibition, “Pièces Détachèes,” or “Spare Parts” in English, offers a clue. Like the rows and racks of spare parts that line a mechanic’s garage, one piece may have come from a certain vehicle, found itself temporarily housed next to a piece from another vehicle, only to find a home in yet another vehicle. If the perspectival lines of the horizons painted onto so many trucks themselves are reflections of the driver’s perspective while on the road, then their appearance in Azarzar’s drawings and sketchbook are only on stop on their road onward. Azarzar builds from his interest in what he calls “vernacular aesthetics,” although here we might also introduce “vehicular aesthetics.” Beyond the obvious play on words, his work does provoke questions of circulation, mobility, and iteration. In earlier works by the artist, he interrogated the principles of Islamic geometry and patterns with the workings of Alan Turing’s “automated machine,” later known as the Turing Machine, linking digital algorithmic pattern production with the random iterative computations of modern automations. Each iteration of an initial symbol departs ever so slightly from the last, ultimately resulting in computational movement. Here, in imitation of how the trucks move both symbols and commodities from one side of Morocco to another, Azarzar’s drawings are the vehicles by which these signs continue their aesthetic circulation.

Installation view, scaffolding, 130 x 120 x 50 cm. (Photo Credits: Nassim Azarzar)

On the notion of vernacular aesthetics, other casual observers of Moroccan contemporary art such as myself, may have noticed a tendency of some artists today to reinvest in the visual and aesthetic language of the country’s artisans of many sorts, as well as the vernaculars of its streets. At times this means recycling, or upcycling, the work of artisans and craftspeople. At other times it means finding, or taking inspiration in such works. What strikes me about Azarzar’s work, even if it may be seen as part of this broader trend, is the work’s frankness in its form of imitation. Like all forms of automated transmission, from facsimile to photocopy, each new iteration, or imitation, leads to decay. A photo sent on WhatsApp is on the road to decay with each new forward. Decay, as odd as it may sound, is inherent to mobility. Azarzar’s work here embraces that decay and does not succumb to the preservationist instinct of salvaging the transmission by placing it in a glass museum box. His are spare parts, mixed and jumbled together and ready to be used again in a new context.

Installation views, coloured-pencil drawings. (Photo Credits: Nassim Azarzar)

Installation views, coloured-pencil drawings. (Photo Credits: Nassim Azarzar)

These remarks, on imitation and decay, could be read as pejorative. I do not intend for them to be, but rather am evoking what French sociologist Gabriel de Tarde spoke of as the three forms by which social and cultural change occurs: innovation, interference, and imitation. Interference and imitation, like decay, are normally understood to be corrupting forces. Here, we might remind ourselves that before a tradition becomes a codified tradition, it is simply a series of imitated practices. This relationship is codified in the Arabic language, between singular and plural forms of the same root and pattern: التقليد والتقاليد. Azarzar ruminated on this relationship in his participation in the 2017 edition of the Youmein Festival in Tangier when he explored the festival’s theme of imitation with a large hanging zilij mural made from photocopied patterns generated by automation, and where I was first introduced to his work. In “Pièces Détachèes,” the artist deepens his commitment to the decaying powers of interference and imitation, raising parole to the formality of langue and not leaving them socially and semiotically disconnected, as the Swiss proto-structuralist linguist Ferdinand de Saussure might have had it.

In closing, we might consider now how these vernacular and vehicular aesthetics will continue to grow and from whence it emerges. Signs, in their essence, exist only in as much as they circulate. Their referential quality may be loose and slippery—a slipping sign only slips until it slides into a new index of meaning—but their movement is integral to their semiotic quality. Bringing together three stages of his work on these signs—the sketchbook, the pencil drawings, and the black scaffolding—Azarzar here invites us to attend to the present qualities of the signs which he has spent considerable energy meticulously documenting as well as imagining their future circulations. Lest we forget: the scaffolding, like the vehicles from whence it circuitously emerged, is also on wheels and ready to roll. Bonne Route!

Dr. A. George Bajalia

is one of the co-founding directors of the Youmein Festival in Tangier, Morocco, and an anthropologist concerned with questions of temporality, borders, semiotics, and the practices and politics of belonging and difference. His current book project, Waiting at the Border: Language, Labor, and Infrastructure in the Strait of Gibraltar, dwells on the political, social, and cultural forms that emerge during time spent waiting among cross-border workers and immigrants living and working around the Moroccan-Spanish borderlands. Bajalia is a professor of Anthropology at Wesleyan University, USA and received his Ph.D. from the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University.