Review #12:

Suni‘a Bisihrika

Farah Sayem in conversation with Tarek Abou El Foutouh, Philip Rizk, and Ala Younis.

صُنِعَ (suni‘a) “was made” or “was crafted” (passive voice of “to make”)

بِـ (bi-) “by” or “through”

سِحْرِكَ (siḥrika) “your magic”

بِـ (bi-) “by” or “through”

سِحْرِكَ (siḥrika) “your magic”

Suni’a Bisihrika is a collective exhibition presented across the Medina of Tunis as part of the Dream City Festival 2025. The exhibition features works by Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Jumana Manna, Walid Raad, Mona Hatoum, Alia Farid, Ayman Zedani, Etel Adnan, Ali Eyal, Ala Younis, Iman Issa, Philip Rizk, Noor Abuarafeh, Sajjad Abbas, Sonia Kallel, Mounir Salah, Saif Fradj, Fredj Moussa, Alla Abdunabi, Haythem Zakaria, and Iman Mersal & Kayfa ta.

The exhibition, curated by Tarek Abou El Fetouh, runs from October 3 to October 19, 2025, in the Medina of Tunis.

The exhibition, curated by Tarek Abou El Fetouh, runs from October 3 to October 19, 2025, in the Medina of Tunis.

The series of maqāmāt has been named “Suni‘a Bisiḥrika صنع بسحرك” to make it easier to memorize. Each letter of these two words corresponds to the first letter of one of the principal maqāmāt. If we consider only seven maqāmāt, the name becomes “Suni‘a Bisiḥr صنع بسحر”: Ṣabā (صبا), Nahāwand (نهاوند), ʿAjam (عجم), Bayāt (بيات), Sīkāh (سيكاه), Ḥijāz (حجاز), Rāst (راست), Kurd (كرد) the eighth added maqām.1

It was a Sunday when I met Tarek Abou El Fetouh over a black coffee and a glass of orange juice in Beb Bhar, Tunis. We decided to have this conversation before I embarked on my tour of his ambitious exhibition program. I admit, I was nervous about completing the entire parcours, but I did and I left deeply moved, energized by the remarkable artworks and the critical thinking they inspired. In the heart of the Medina of Tunis, Suni‘a Bisihrika unfolds as a resonant field of memory, a landscape to be walked and inhabited. Conceived by Abou El Fetouh for Dream City 2025, the project transforms the Medina into a living score, where each artwork performs a fragment of collective history. For over two decades, Abou El Fetouh has developed a curatorial practice rooted in dialogue and displacement. His work, spanning Cairo, Sharjah, Beijing, and Warsaw, consistently navigates the intersections of performance, politics, and memory. Landmark projects such as Lest the Two Seas Meet (Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, 2015), Time is Out of Joint (Sharjah and Gwangju Biennials, 2016), and Abdullah Al Saadi: Sites for Memory… Sites for Forgetting (UAE Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2024) reflect his sustained engagement with transnational art histories and the poetics of migration. As founder of YATF (The Young Arab Theatre Fund) now Mophradat, he has fostered a networked, experimental Arab art scene capable of moving beyond national boundaries.

Dream Exhibition ©Pol Guillard

Curating through the Maqâm: Listening to History Otherwise

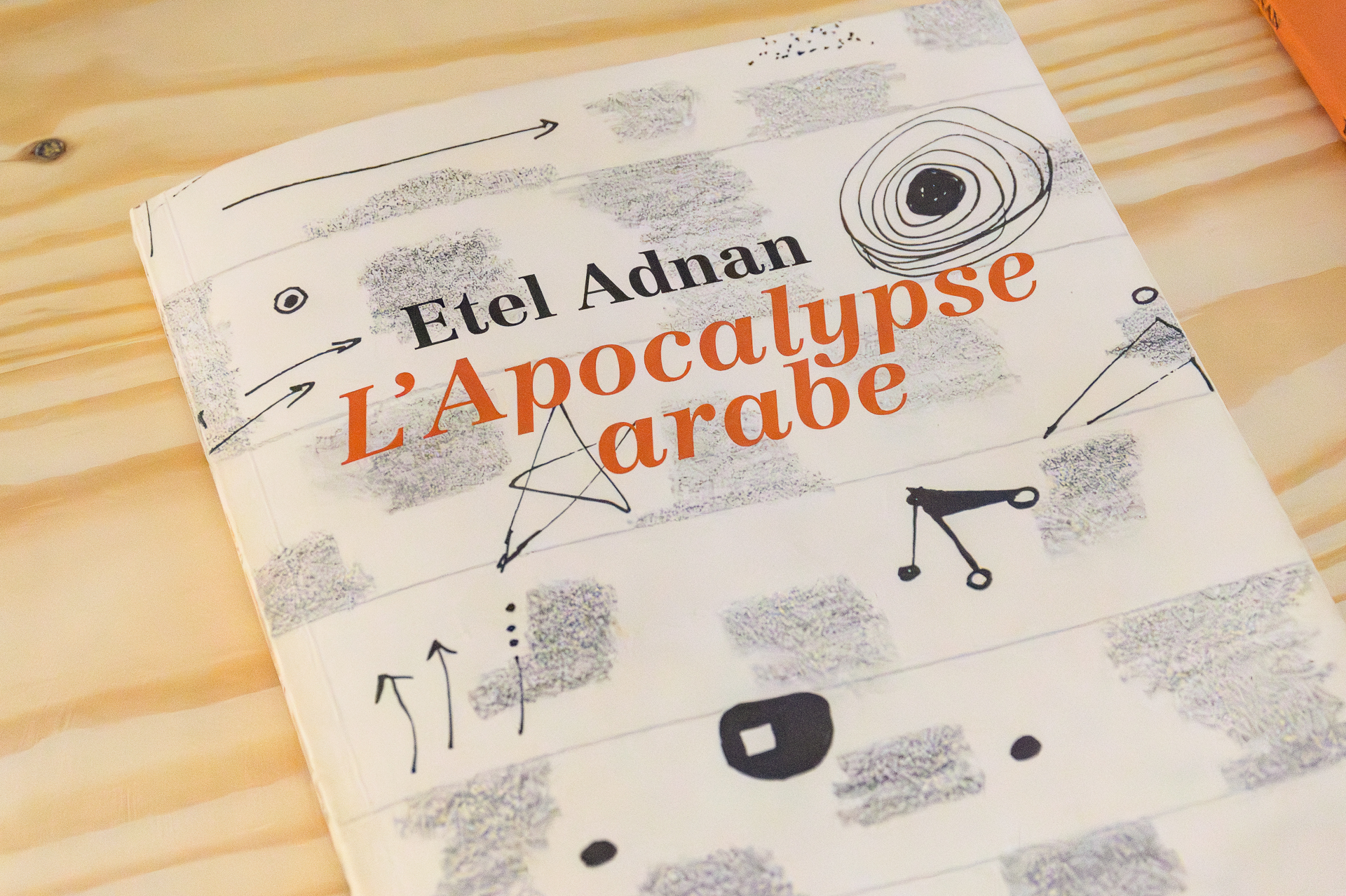

The exhibition unfolds across ten historical buildings and eight cafés, each one associated with a specific maqâm, the melodic mode that structures Arabic musical composition. For Abou El Fetouh, the maqâm is an ecosystem of acoustic archives of encounters between Kurdish, Persian, Andalusian, Amazigh, and Ottoman traditions. Through the maqâm, one can trace centuries of circulation of gestures that survived empire, colonization, and exile. The curator proposes a counter-history to the modern notion of “Arab music,” standardized during the 1932 Congress of Arab Music. Prepared in part in Tunis under the patronage of Baron d’Erlanger, that congress sought to codify a singular Arab identity at a moment of geopolitical realignment. Within this framework, the Medina itself becomes a body of sound. The cafés of Bab Souika, Taht Essour, and El Abbassia turn into listening posts. Each site within Suni‘a Bisihrika carries its own resonance. Dar Doghri and the former Al Hamra Cinema, built in 1922, embody the shared Andalusian imaginary that once linked Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad. The works exhibited within them form a dispersed orchestra of voices: Measures of Distance (1988) by Mona Hatoum dialogues with Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse, newly reissued in Arabic, while new commissions created in Tunis respond to both the space and the sonic archive of the city. I think strongly that Abou El Fetouh composes an urban symphony where memory and architecture merge. “Everything changes and is destroyed except music; music remains,” he says.

Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse ©Pol Guillard

Throughout my tour of the artworks, I felt that the exhibition’s rhythm follows the historical vibrations of the Arab world, including the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, colonial ruptures, and contemporary wars. Its sonic architecture resonates with places of displacement and resistance: Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and territories where art continues to articulate what politics cannot contain. It gathers artists who recompose memory through different mediums. In Ismyrna (2016), Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige revisit the memory of Smyrna (now Izmir) with Etel Adnan, exploring exile and loss through dialogue. Noor Abuarafeh’s new publication, If I Don’t Whisper, I Will Forget (2025), blends letters to her child with recipes and recollections of tender documents of survival amid war and famine. Mounir Salah’s To Hell With Art (2025) resurrects the censored songs of Iraqi artist Aziz Ali, whose voice reemerges in the uprisings of Baghdad. Other artworks engage with myth and extinction. Ala Abdunabi’s salt sculpture I Endured for You (2025), evokes the vanished Barbary lion as an allegory of North African memory. Abou El Fetouh’s curatorial approach exposes the mechanisms of erasure, the ways in which art and sound can resist homogenization. By situating artworks in cinemas, libraries, and mausoleums, the exhibition reclaims spaces where the institutional and the popular, the sacred and the everyday, coexist.

About Philip Rizk (Egypt) in Suni’a Bisihrika and beyond…

Among the artists featured in the exhibition, Philip Rizk’s artwork caught my attention with its cinematic language and its ability to entangle politics and imagination. Our discussion began simply as a brief exchange about language and context, but soon unfolded into a reflection on his interdisciplinary journey. “I’m an artist, filmmaker, and writer. My background is in philosophy, Middle East studies, and anthropology. I didn’t study art or filmmaking formally, I learned by doing,” he told me. Rizk’s first film, Sumud (2009), explores the principle of sumud, Palestinian steadfastness, as a form of resistance and presence on the land. His early artistic trajectory intertwined with activism, during the Egyptian revolution, he was part of the Mosireen collective that produced and circulated hundreds of videos documenting the uprising. His subsequent collaboration with Jasmina Metwaly on Barra fil-sharia (Out on the Street) invited ten Egyptian workers to perform their own stories about labor and privatization. What if workers could reclaim control over their means of production? This is the question that the film asks. The work was presented at major international platforms, including the Berlinale (2015) and the Venice Biennale (2015), and was recently screened in Tunis at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. At Dream City 2025, Rizk presented Mapping Lessons (the lessons), an installation version of his film Mapping Lessons (2020) that reflects his ongoing inquiry into autonomy and collective learning. The project draws from the Syrian Revolution, an exercise in imagining what people can learn from self-organized communities. The work is presented as eight lessons and projected onto classroom blackboards in a former school in downtown Tunis. The installation invites viewers to reflect on education, finding alternative sources of energy under siege, and collective survival in contexts of oppression. “In one room, you see how people built solar ovens or imagined schools outside of state control. In the other, the focus shifts to historical continuities, the persistence of colonial and neo-colonial systems shaping our present,” Rizk explained. His research-driven practice extends into Terrible Sounds, a triptych (2022) that revisits the 1932 Congress of Arab Music in Cairo, a historical moment when the king of Egypt sought to redefine the music of the Arabic-speaking region according to European standards. Working with musicians from Cairo, Alexandria, and Beirut, Rizk reimagines this lost improvisational spirit, positioning sound as both resistance and memory. Later works, including Terror Tales (2024) and Land Listening (2025), deepen his exploration of the region’s political ecologies, the latter focusing on Nubian cosmologies and their intertwined relationship with the Nile. “I wanted to challenge this inherited colonial mentality that places humans above nature, and instead recall older ways of living alongside it,” he said.

Work by Philip Rizk ©Pol Guillard

Exhibiting in Tunis was a return and a renewal for Philip, “It has always been a priority for me to show my work in the region. The political and aesthetic complexity of my films doesn’t always fit in traditional festival formats, but here there is genuine curiosity for this kind of practice.”

Ala Younis (Jordan) From Haifa street شارع حيفا in Baghdad to Glacier street نهج فَـرِبْكَة الثلج in the Médina of Tunis!

Ala Younis’ artwork likewise stood out to me for the clarity of its context and the depth of its historical resonance. Her practice unfolds with a rare precision, it weaves together art and historiography to interrogate how architecture and politics co-construct modernity in the Arab world. Younis witnessed the movement of Iraqi architects and artists into Jordan and the transformation this brought to local artistic discourse. “Everything about architecture for me starts from that period, from the exchanges between displaced architects, the stories that circulated with them, and the transition from Baghdad to Amman.” She said at the beginning of our discussion. In the practice of Ala Younis, architecture is a repository of memory and political transition. Trained as an architect in Amman during the turbulent years following the Gulf War, Younis came of age within a generation whose understanding of the built environment was inseparable from the shifting geographies of displacement and reconstruction that reshaped the Arab world in the 1990s. During her studies in Jordan, Younis witnessed a regional migration of architects, artists, and intellectuals fleeing from Kuwait and Iraq into Jordan, forming temporary networks of collaboration and pedagogy. The architectural discourse of her generation was shaped by the legacies of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, yet filtered through the vernacular modernism of figures like Hassan Fathy and Rifaat Chadirji. Her disinterest in the commercial architecture of the market led her to reimagine how architecture might serve as an archive of collective aspiration and trauma.

Work by Ala Younis ©Pol Guillard

A pivotal discovery came in 2010, when Younis encountered an image of a Le Corbusier-designed building in Baghdad, an architectural ghost absent from both her education and the public record. The building’s obscurity prompted an extended inquiry into the architectural history of Baghdad, revealing forgotten projects like Haifa Street شارع حيفا (Shar’a Haifa), a monumental urban plan executed during the 1980s that embodied the ambitions of Iraq’s modernist era. Through extensive archival research, Younis uncovered the entangled histories of local and foreign architects and the geopolitical networks that facilitated these constructions. In the process, she reframed Baghdad’s modern architecture as a complex cultural palimpsest where utopian design, political propaganda, and the lived realities of war coexist in uneasy tension. Younis Haifa Street project examines the urban fabric of this site as both a physical and symbolic space.

Conceived during an era of oil-fueled modernization and later ravaged by conflict, the street stands as a condensed chronicle of Iraq’s twentieth-century history. Its residential towers, government buildings, and public institutions were at once expressions of civic pride and instruments of control. Her research extends beyond the architectural object to the question of representation: how has the image of these buildings been mediated, and by whom? The artist notes that most available photographs of Haifa Street depict its exterior monuments of state authority or ruins of occupation, while interior views publicly surface first through military documentation. In Younis installations in Glacier street نهج فَـرِبْكَة الثلج in the Médina of Tunis, this tension between the seen and the unseen becomes a critical strategy. The interior, occupied by foreign soldiers or abandoned by its residents, becomes a metaphor for the invisible histories embedded in the material structure. The commissions that shaped Baghdad’s skyline in the 1970s and 1980s were often executed by foreign firms Japanese, Korean, German, Eastern European yet they responded to local design visions articulated by figures such as Chadirji, Maath Alousi, and Hisham Madfa‘i. Younis engages the memory of Iraqi artist Nuha al-Radi, whose public artworks and writings from the time of the Gulf War resonate with the artist's reconstruction of the street’s narrative. Radi’s nightmares of the American invasion of Baghdad merge with Younis re-creation of those images, layering fact and fiction in a shared visual memory of loss, and occupation.

A Geography of Circulation

Suni‘a Bisihrika will travel to Beirut, Damascus, Jeddah, and Baghdad before returning to Tunis in 2027, following the migratory paths of the maqâms themselves. Each city will host new works, new voices, a constantly expanding constellation of listening. It is a curatorial gesture of reconnection. It reopens the routes that once linked these cities through trade, and songs fragmented by war and nationalism.

Work by Haythem Zakaria ©Pol Guillard

Footnotes

1 A website for teaching Arabic maqāmā: oudline

Farah Sayem (b. 1996) is a Tunis-based curator and cultural practitioner whose work explores the physical and political dimensions of urban and common spaces, examining their social and cultural dynamics as tools for transformation and resistance to neoliberalism. Since 2020, she has developed cultural projects promoting the democratization of art in public spaces, collaborating with L’Art Rue (Dream City), UN Women, Collectif Créatif, La Boîte, Gabes Cinema Fen, and El Warcha. She holds master’s degrees in Product Design and Social & Solidarity Management, was part of TASAWAR Curatorial Studios 3, and is currently a PhD researcher (IRG) at Université Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée – Gustave Eiffel.