Review #1: The Nutshell

Dina Jereidini

“The Nutshell” is a group show featuring the work of Hany Rashed, Yasmine ElMeleegy, Alaa Abdelhamid and Ahmed Shawky Hassan and runs at Access Art Space in Downtown Cairo from May 15th to June 15th of 2022.

In reviewing this show, I was met with an abundance of references (and referentiality); an abundance of physical space, of affective and efficacious excess. And although abundance drew me to this artist-organised exhibition, it also contributed to an antagonistic push-back. And so I pushed forward, and from that initial position stems a few observations and realisations.

First, that each of the artists willfully utilizes their space with a liberty only offered when one is or seems to be at a conceptual crossroads within their work. Second, that upon closer examination one senses a sort of yearning, present and shared within the four artists’ work.

The first room hosts three artworks by Ahmed Shawky Hassan, who has a longtime practice of critiquing ways of institutional representation. In approaching his most recent work, one is immediately struck by the visual language of the internet in the pieces; for example chat boxes, paintings and gifs.

The artworks sit side by side in a coordinated color scheme of blues, greys, reds and yellows. Their HEX codes are appropriated from official regulations and colors of renowned auction houses and museums, which the artist himself dissects.

“How to become a standard audience”, 2022.

“Please touch history carefully”, 2022

In “How to become a standard audience?” (2022) Hassan sets up a hypothetical conversation with an AI chat bot. The conversation attempts to uncover features typically attributed to stock-images audience members find on gallery instagram accounts. By asking just how one becomes a standard audience member. Hassan uncovers a laundry list of convoluted answers, culminating in the bot-described objective of facilitating the ‘purchase’ of the artwork. Calling into question the role of the audience within these institutions, Hassan achieves this further through a ‘spot-the-difference’ series depicting the real-life assassination of Andrei Karlov, Russian Ambassador to Turkey at an exhibition opening. Rendering audience engagement and presence as an essential form of labor, Hassan now turns to the language of visual representation used to target these essential workers. In “Please touch history carefully,” he re-frames a white-gloved art handler iStock photo which is used to litter the instagram feeds of major institutions into a cannibalizing infinite loop.

Hassan’s interests seem to have shifted, from the Egyptian, analogue, and institutional context into a decentralized and increasingly digital ‘gaze-as-context’ approach. He is currently rather interested in critiquing a ‘globalized’ art market dominated by few key players and their predominantly online contemporary presence, mediated by account managers and the newly invented class of social media executives. Hassan wonders, what value does this market derive from the unpaid labor of the audience?

Works by

Hany Rashed

Works by

Hany Rashed

In the second and third room, Hany Rashed crafts an entirely different exhibition experience. Floor to ceiling memes, rendered in thick strokes of acrylic paint shock and unsettle, many with hilarious painted text-on-image to boot. Some are small, some are the size of large windows, the paintings are littered with images and references to popular culture, from Bee Movie to pudgy grotesque internet babies, and Facebook Messenger stickers. Meme-phrases such as “Ya rab el sho’3l yemoot,” and “Sabahkom Gameel,” unlock memories of a time when proudly displaying shared collective sympathies on the status quo was new online, and distinctly liberating.

It seems Rashed is attempting something here which is almost unceremonious. Is he seeking nostalgia? Or is this a manifestation of some rote archival impulse? As sincerity and irony meld together, I am met with an entirely new set of questions; are these artworks really a discursive final point? A desire to call a thing what it is? When their digital counterparts are so easy to create that they can be churned out in the millions at unfathomable speeds, what does this mean for what we create?

I was pleasantly surprised when I began to notice the artworks reintroduced into the digisphere via a series of instagram posts. As an artist whose practice is composed simultaneously of two distinct theatrical stages: the online stage, and the more traditional gallery space, it is not unusual for Rashed to bridge the online and offline in his work. And so the artworks’ online presence became part of the work for me. A reminder that an artifact of the internet, once reproduced, does not remain static.

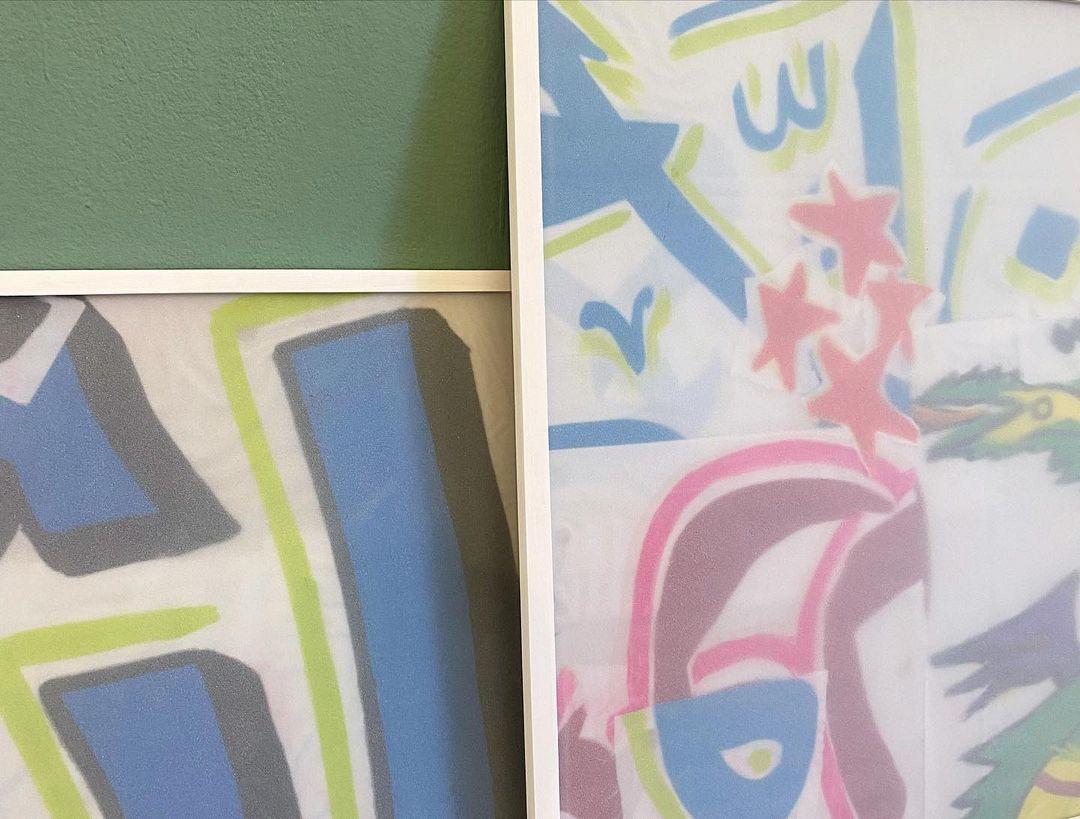

“The six hundred seventy four forms and a dragon”, 2022.

“The six hundred seventy four forms and a dragon”, 2022.

In the fourth room, you can find Yasmine ElMeleegy’s “The six hundred seventy four forms and a dragon” (2022). From one piece of archival footage, ElMeleegy has spun a narrative of history, craft, labor and representation. When she comes across a video of the 2013 Egyptian protest against agrochemical leviathan Monsanto, questions begin to arise for ElMeleegy. Seeing the links between the ethos of the demonstrations and her own work in “Future Farms” (2013–present), ElMeleegy got to work.

“The six hundred seventy four forms and a dragon” presents a fragmented tale of 674 monopolized genetically-modified seeds controlled by a giant paper mache dragon. Recreated and repainted into quasi-political election signage, ElMeleegy then cuts the fabric signs up into dozens of smaller bits and pieces, and reframes them for dramatic effect. Her choice of display is meant to signify the failure of such cries against monopolizing powers, as the frames sit vertically against the walls in frosted white frames, unhung. The visual language of these signs ElMeleegy delegates and attributes entirely to one man: Mostafa ElKady, her sign maker, as he himself practices and preserves a long lived tradition of sign-making in Egypt.

In her work, ElMeleegy often preserves the practices of others in a kind of patronage. She has previously worked alongside bronze statue-makers, pharmacy-owners, and now a political-banner-maker. Her practice of reviving these people’s methodologies of work can be seen as a tribute to the historical, and to their once necessary functions. And while “Future Farms’’ beginnings were nestled in a commentary on grotesque mis-steps by authority—determining what we eat, making poor hygienic and health decisions for entire populations—in maintaining the practices of those whose labor once kept authorities in check, it continues to be so.

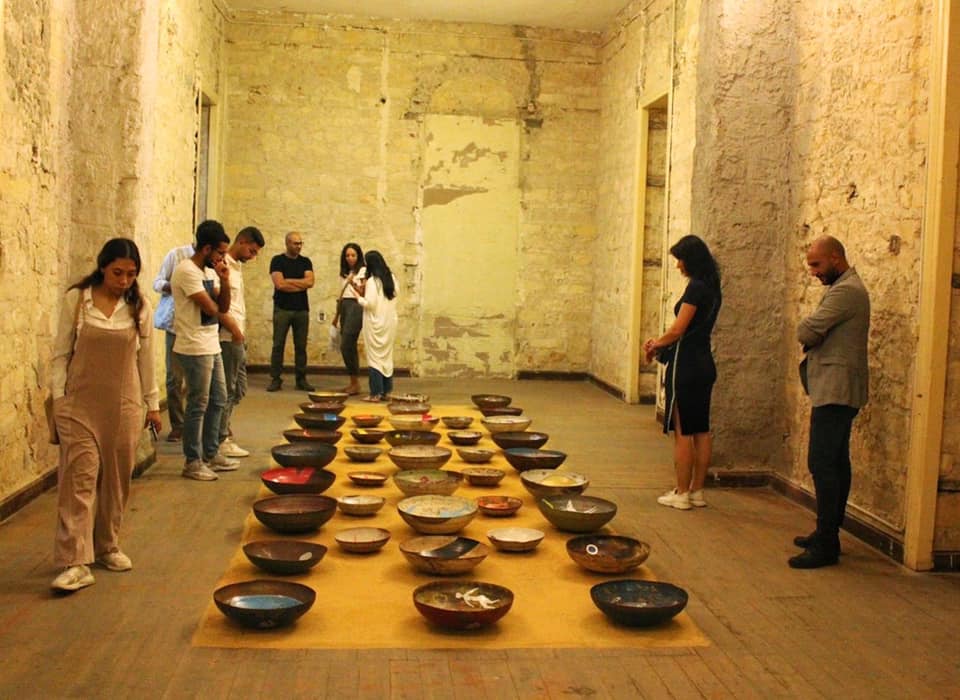

“I wish I could stand that hideous aesthetics”, 2022

In the fifth and final room, there is a strange sense of space. This is partly due to the introduction of bare-brick walls, and partly due to something else. An installation of 39 painted bowls titled “I wish I could stand that hideous aesthetics” 2014–2022 lies on the ground in a rectangular patch of yellow sand, with the 40th bowl hanging solely on the adjacent wall. Alaa Abdelhamid's work centers on a critique of contemporary notions of primitivism. His tongue-in-cheek collection of bowls gives us a hint as what the artist deems “a statement on the aesthetics of the Egyptian art market.” With the deified essentialist purity of the art market, the resulting primitivist-style aesthetics demands to be contended with; by its artists, as members and producers within that market. It is in having to contend with these dominant aesthetics that Abdelhamid finds himself making these bowls on the fringes of his day-to-day artist practice.

Despite prevailing notions surrounding primitivist aesthetics as problematic, brought about via western imperialism and often with racist connotations, Abdelhamid embraces the work, saying; “in a way the work is about how to reconcile with the work, of feeling like it isn't mine.” The work invites criticism, creating a somewhat off-putting reaction, which he embraces. “I wish I could stand that hideous aesthetics” effectively delivers on its name.

What I find shared between all of the artworks in this show is a sort of impulse towards inertia; a desire to take a discursive look back at a still-living, still-mutating past. Whether by readily welcoming the status quo and transforming it into a type of machination for critiquing the system from within, or by using its representational tools to turn implicit biases explicit. If there is any true complicity here it may be due to the complicit nature of the market in which these artists find themselves, as their yearning for agency turns into something more tangible and often colorful; tributes to a living archive.

Dina Jereidini is a visual artist, writer and curator based in Cairo, Egypt. Their work explores the translation of information into physical form as a universal attribute of the mental and material world. Their practice is multidisciplinary, utilizing text, 3D art, performance, audio, painting, woodworking and sculpture.