When the Museum was Melting

Text and drawings by Ahmed Shawky Hassan

In an alleged protest against those who do not shed enough light on the safety of the planet and the climate and environmental changes that may lead humanity towards a direct threat, a man dressed as an old lady was caught jumping out of a wheelchair attempting to smear the bulletproof glass covering the Mona Lisa with a piece of ice cream, that was especially imported from the Philippines, and had a sweet, earthy flavour and a bright purple colour that makes it perfect for an Instagram post.

Note: In 2019, the Louvre Museum renovated the Mona Lisa exhibition room, equipping it with an advanced security system that ensures unparalleled protection. The painting was displayed inside a sealed, multi-layered, anti-glare, anti-reflective, and lead-proof glass case. In addition to that, it comes with a climate and stability system that controls the humidity and purification of air inside the case.

At that moment, the perpetrator of the accident succeeded in grabbing everyone's attention, by spreading a state of tension and confusion that overwhelmed everyone in the museum. He opened a window full of curiosity in their minds; why did he commit that act and implicate everyone in this context? When such anti-museum protests occur unexpectedly, it compels the audience to seek questions about their position from the future; to what extent is it possible to ask such a question in an institution concerned with history-making? And why did that man choose to come here at a critical moment during peak hours, and vandalise the artwork in front of a huge crowd, instead of at a later hour when visitors are dispersed or when the museum is closed? Why did he choose this specific institution and not another place directly related to the topic of the environment and climate? Noting that the museum is one of the institutions that took the initiative in the twenty-first century to transform its professional practices and structural systems to be in line with the issue of sustainable development and climate change. Additionally, museums around the world are launching open calls and commissioning invitations as contributions to financing and producing art projects that support environmental issues, and this can easily be found out by browsing their official websites on the internet.

So, why are museums especially targeted by climate and environmental activists?

Moments before that incident, I was at the forefront of the ranks, a short distance from the perpetrator. We almost touched each other due to the intensity of the crowd's jostling. I was afraid that fate would lead me to a misunderstanding that might implicate me with him, so I quickly copied everyone and took out my phone; I opened the live broadcast on Instagram, and I gave it a press to start filming.

I was in this stiff posture for a few minutes until the museum’s security arrived and immediately arrested the person, taking him out of the museum. I discovered while I was standing there that this was my first encounter with broadcasting live on social media. How precious was that experience!

How could this coincidence lead me to such an exciting feeling? I felt as if I was taking part in a heroic act; like a freelance photographer who risked their life to cover the Vietnam War to tell the truth beyond broadcast television, when Sony invented the first portable video camera (Portapak) and made it available as a new affordable commodity.

This is how millions of people around the world were able, through social media networks, to follow the incident of the Mona Lisa being smeared with ice cream, moment by moment, as if they were with us here in the museum. But they really were! By making this live broadcast available on Instagram, I contributed to the expansion of the museum’s space from its physical surroundings, to extend and include every context in which it operates on a mobile phone. Thus, thanks to me, the world turned into a museum space that has never been seen before.

After the incident was over, the Mona Lisa showroom was immediately shut for maintenance work, an inspection of the security system, and the detection of any loopholes to prevent similar actions from occurring in the future. The museum then announced its reopening, where anyone with a smartphone in their hand raced to attend, so that they can share a live broadcast of the moment the painting appears to the public again.

Before the opening date, the museum held a press conference under the title “Mona Lisa Always and Forever”, where one of the curators working in the museum appeared in an elegant black suit wearing white gloves. He held a microphone connected to the central speakers, and began to give a speech to the journalists on the history of the Mona Lisa, from the moment of its production, to all the accidents it went through and how it withstood them. He continued till he brought us to the current moment, after completing an hour of continuous non-stop speaking, ending with a sentence where his voice swelled and shrieked as he said:

“And always remember that you are standing in a very safe space... Now the moment we have all been waiting for has come, the new Mona Lisa will be unveiled - Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece...?!”

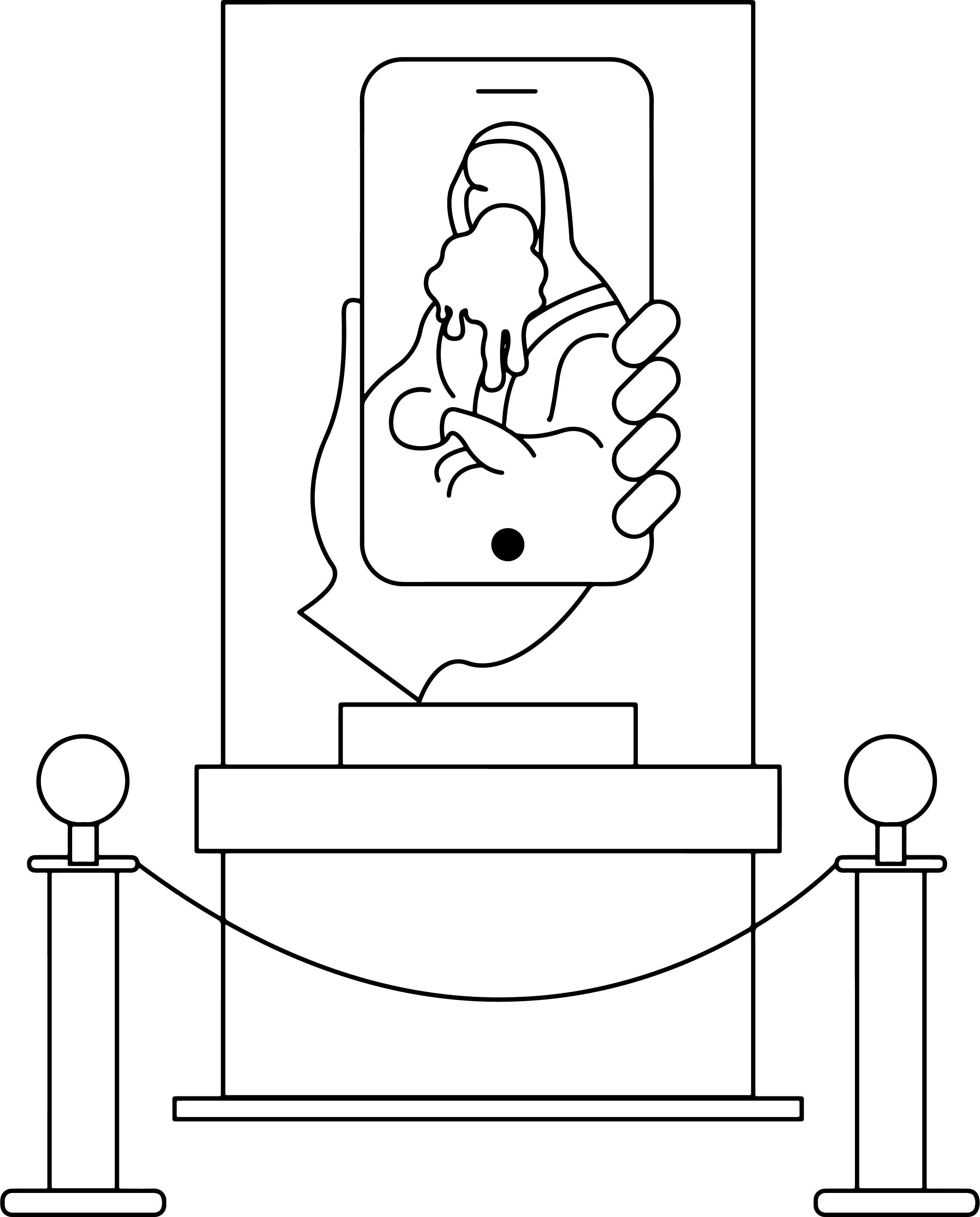

The curtain was lifted indeed, and the audience was surprised that the Mona Lisa was not in her place behind the barriers in her glass box. It was rather replaced by an amputated hand holding a smartphone, showing a live broadcast of the incident of her being smeared with ice cream.

At that moment, I became aware of the importance of the role I presented to the world, especially when the circles of capital, thanks to which museums sustain themselves, gathered to make a final decision to acquire and showcase me, as I have become an integral part of the museum collection. I had already succeeded in reaching an agreement with the person whose body I belong to, and he decided to separate me from him in return for an appropriate amount of money for the amputation process, which was determined by a committee of experts in the world of museums. What absolute freedom and exclusivity! I have now become the first ever disembodied hand to be acquired by a museum, holding a smartphone between my fingers, broadcasting live anti-museum protests. This is how they introduced me to the world.

When the curtain was lifted, I was born with an extreme euphoria towards fame. My picture filled the covers of art magazines and circulated on the internet. Certainly, that event sparked widespread controversy. There is no page concerned with art and its history on social media networks without at least a meme bearing my picture. Visitors now go to the museum, queue in line for hours, to see the hand holding a smartphone between its fingers, which transmits the live broadcast of the ice cream incident.

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

An excerpt from a press conference w ith the hand holding the smartphone between its fingers, responsible for the live broadcast of museum protests:

– In your opinion, why do environmental activists choose museums through which they can announce and direct their messages to the world, and not institutions more related to the cause such as oil companies, for example? Or to phrase it differently, do the perpetrators of such incidents understand the value of the artworks they attempt to vandalise?

“It is not necessary for them to be well-versed in art history in order to commit such acts. It is sufficient enough that everyone acknowledges the museum as a sacred place, making it a magical medium where people unite in defending it and its contents. It is simply a place that has a set of rules and concepts that countries and people cannot abandon, like civilisation, history, identity, belonging, leadership, existence, etc., all of which make it suitable for mobilisation and release of statements.”

– Do you think, from your point of view, that you actually defeated the Mona Lisa by sitting in her place despite all her historical fame?

“Of course not! We are both phenomena in which the image of art was manifested.”

– What does it mean for the cleaners who have to get burdened with additional work, such as cleaning the traces of similar anti-museum acts?

“Before we get into the importance of the definition of labour and workers' rights in this context, do you first know how museums economies work? And the extent of its benefit from the occurrence of such facts and actions?”

– Isn't your comparison with the Mona Lisa fair to you? For you certainly do not have the amount of artistic skill nor the historical value that she has to replace her?

“What artistic value?! Do you really mean what you are saying? The curtain unveiling of my presence in the museum, instead of the Mona Lisa, became a declaration of the failure of art to compete with its institutional image in the public. In this specific context, I mean the institutional image that museums have created during the past few decades, from the moment it was realised as a virtual space on the internet. This acts as a factory for the production of millions of images of art daily, whether official or unofficial. Examples include images leaked from surveillance cameras or officially published in the media or on social media platforms, both of which are forms of liquidity through which there is an institutional and media expansion for the term art, which can extend and expand to include—and even devour—everything around it, even including the audience itself.”

– Amidst acts of vandalism against museums, is there a possibility that if they increase or appear in other forms, they will succeed again in destroying this world?

“On the contrary, the history of art has proven that such acts committed against museums are museum acts themselves.”

– Although eliminating environmental degradation, which includes climate change issues and others, is an inherent human right; are you for or against vandalism in museums?

“I feel confused about the matter to be honest, because I lived all my life—until the Mona Lisa ice cream smearing incident and the consequent amputation—as a left hand of a body that dealt with museums as a model of a multi-layered bureaucratic work environment. This space supposedly does not permit visitors with ice cream, not smartphones. Therefore, the mere idea of looking at artworks with an ice cream in hand that can melt on the grounds of the museum, is something I see as a privilege enjoyed by the perpetrator of the act. My judgement will thus be biased and unfair to him, because as a matter of fact, it never occurred to me that I would one day be able to walk into a museum with a phone in hand, transmitting a live feed of someone smearing an artwork with ice cream without a permit to photograph.”

– So do you think that the perpetrator of that act has the privilege or luxury to do it?

“Yes and no! Somewhere between yes and no, people have varying areas of awareness of the context and the amount of privilege.”

– Last question: What happened to the person you belonged to?

“The person was here on a business trip, and after we separated, before he travelled home, he told his story to the media. As they got more interested in him, he gave more interviews and started making more money than he ever did. The more interviews he gets, the stronger his chance of a future better than his past life—everyone here is incredibly curious about the case of the first-ever museum-acquired hand holding a smartphone between its fingers broadcasting a live anti-museum protest.”

Ahmed Shawky Hassan is an artist and writer, Born in 1989 in Ismailia, Egypt. His practice examines the affects and effects of current and historical narratives of the arts, through the investigation of their manifestations and proliferation in the current art sphere. Through text, objects, video and drawing he invites the viewer to explore these hidden and unofficial narratives in the gallery, studio and museum hall. While questioning the roles of the curator, artist, and the viewer as complicit in the preconceived assumptions around artwork and space. Shawky Hassan has recently published his first book “The Video Museum”. Shawky Hassan received his BA from the Faculty of Art Education at Cairo’s Helwan University in 2011. He worked as co-director of MHWLN (a research group devoted to researching and reflecting on the history of contemporary art in Egypt) in 2016 and 2017.